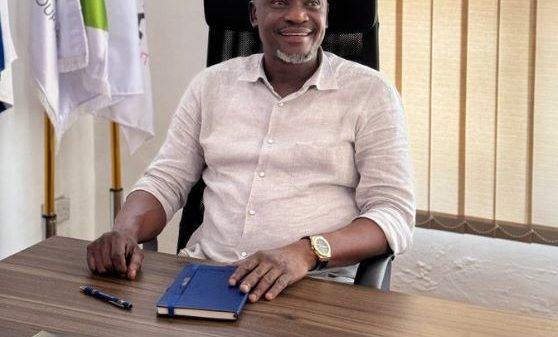

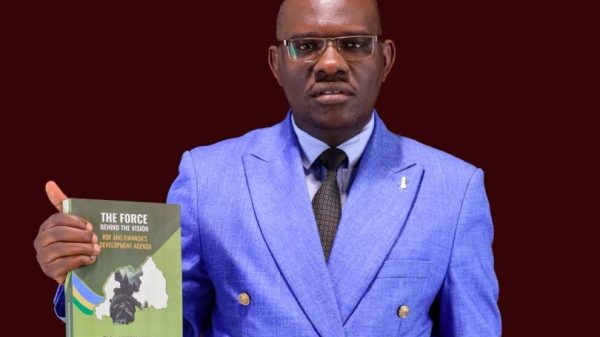

Commentary by Dr. Joseph Nkurunziza Ryarasa

I have come to accept the wisdom behind the idea that if you do not learn from history, history will almost certainly repeat itself. Over the weekend, as I spent time reviewing the growing food insecurity in parts of Kayonza District, I felt a familiar unease.

I have come to accept the wisdom behind the idea that if you do not learn from history, history will almost certainly repeat itself. Over the weekend, as I spent time reviewing the growing food insecurity in parts of Kayonza District, I felt a familiar unease.

The patterns emerging in sectors like Ndego and Kabare reminded me of a place that shaped both my career and my understanding of how communities can rise from deep vulnerability.

After graduating from University of Rwanda, I began my public health career in Mayange Sector in Bugesera district. I was based at Mayange Health Centre, yet my work quickly grew beyond routine health service delivery when I joined the Millennium Villages Project as a health coordinator, a Columbia University initiative led globally by Jeffrey Sachs and implemented in Rwanda under the direction of Josh Ruxin.

By then Mayange had a population of about thirty thousand people and carried the burden of hunger, chronic drought, poor soils, and persistent poverty. For many households, food insecurity was not a seasonal shock but a defining feature of life.

Beneath those hardships, however, was a remarkable desire to progress. The Millennium Villages Project recognized that hunger is never just the absence of food. It is a symptom of multiple, interconnected challenges: depleted soils, poor health outcomes, limited access to markets, weak infrastructure, and the lack of financial tools that allow families to invest and recover from shocks.

The transformation we witnessed in Mayange over the years came from addressing these issues simultaneously rather than treating them as isolated problems. Agriculture improved through better seeds, small-scale irrigation, farmer training, and soil fertility management. Agroforestry restored ecological balance, bringing shade, nutrients, and biodiversity back to land many had thought was beyond repair.

At the same time, improvements in maternal and child health took root. Community health workers were better trained and equipped, nutrition support expanded, and emergency referral systems became more responsive.

Roads and water infrastructure reduced the time and energy households spent simply to survive, allowing them to focus on productive activities. As these interventions complemented one another, something profound happened. Hope returned.

Visitors from across the world came to observe the transformation, and I repeatedly found myself narrating the story of Mayange to delegations eager to understand how a community that had once been a symbol of vulnerability could become a reference point for resilience and integrated rural development.

When the project closed in 2020, it had demonstrated not only that food insecurity can be reversed but that this reversal is most effective when development is multisectoral, long-term, and anchored in local ownership. It is no surprise that lessons from this experience contributed to shaping the Vision Umurenge Programme and other national social protection strategies.

Reflecting on this past, I found the situation in Kayonza troubling. The same early warning signs are appearing. Crops are being lost to erratic rainfall, households are adopting emergency coping strategies such as reducing meals or selling livestock, soils are exhausted, and youth migration is leaving farms unattended. Most visibly, interventions across sectors are not synchronized, repeating the old pattern of fragmented efforts that struggle to achieve lasting impact.

This raises a difficult but necessary question. If we already know what worked in Mayange, why are we not applying those lessons to the districts that EICV7 has clearly identified as the most vulnerable to poverty, food insecurity, and climate shocks?

The data is already pointing to pressure zones in districts such as Nyamagabe, Nyaruguru, Gisagara, Kayonza, Ngoma, Nyagatare, and parts of Karongi and Rubavu. These are areas where poverty remains high, climatic stress is increasing, and agricultural productivity is inconsistent. They mirror, in many ways, the realities Mayange faced in the early 2000s.

Re-adapting the Millennium Villages Project model could provide a structured pathway for these districts. This means not simply replicating the project as it was but updating it for today’s realities such as digital agriculture, climate-smart technologies, cooperative strengthening, community savings systems like Igiceri, youth agribusiness incubation, and local value chain development.

What made Mayange successful was not the scale of the investment but the integration. Agriculture, health, infrastructure, environment, and livelihoods were strengthened together, advancing the community as a whole.

What happened in Mayange was not a miracle. It was a deliberate, coordinated effort supported by evidence, community ownership, and long-term commitment. The warning signs in Kayonza show that history is speaking to us again.

The real measure of leadership is whether we listen, whether we translate our past lessons into present action, and whether we turn proven models into national strategies that ensure no district remains trapped in cycles of hunger and vulnerability.

Rwanda has already shown what works. The challenge now is to apply it where it is most needed.