Munezero Jeanne d’Arc

Those identified by history as historically marginalized are among the groups that still hold backward views regarding gender-based violence against adolescent girls.

Many of these girls are sexually abused and end up with unwanted pregnancies; others are married off before reaching the legal age. In some cases, the abuse is perpetrated by their own parents or brothers.

Seeking justice for these girls remains a major challenge because their cultural background often acts as a barrier. As a result, the abuse is tolerated or normalized, leading to long-term consequences such as dropping out of school and the inability to fulfill their dreams.

“A heartbreaking testimony”

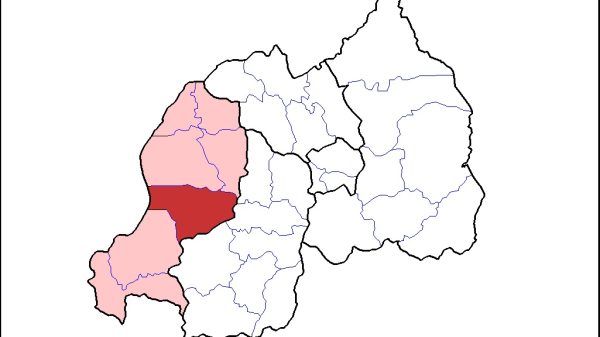

Byukusenge Monique, a 19-year-old girl from Kinyana Village, Kinyana Cell, Masoro Sector, was born to parents from a historically marginalized community. She was sexually abused and became pregnant at the age of 15. Today, she is a mother of two. She says she dropped out of school in Primary Three after getting pregnant by a man she worked with in a stone quarry. Her second child was fathered by her uncle.

When it happened, she informed her parents, but they did nothing. Instead, the man who impregnated her began buying alcohol for her parents, and they drank together. They agreed that he would help raise the child, but the case was never reported to any authorities — she was denied justice.

In her heartbreaking testimony, she says: “I have a mother, but she’s a drunkard. She used to take me to bars, and once we were drunk, she would give me to men to sleep with. Later, I got pregnant by a man I worked with in the quarry. When my family found out I was pregnant, they asked who was responsible. I told them, and they simply sat with him, drinking.

They discussed it and decided I would stay home, and he would support the child. Since he had money and didn’t want to marry a girl from a marginalized group, they kept it a secret so his relatives wouldn’t mock him.

I dropped out of school. I was already performing poorly and used to skip classes to go find clay. I never returned. It destroyed me.

Now I live a very hard life doing physically demanding work because he refused to help me. And my parents told me, ‘No Mutwa ever crosses tradition.’

I never went to the hospital. I gave birth at home. My second child’s father is my own uncle.”

She further stated that being abused and not receiving justice is deeply rooted in the cultural norms and the history in which they were raised — factors that continue to oppress them and cause long-lasting consequences. These include social exclusion, inability to attend school like other children, and passing the same hardships to their own children. All of this leads to severe emotional trauma and lasting shame.

Byukusenge says that even today, they are not valued like other Rwandans, as they are constantly called by all sorts of derogatory names. No young man considers marrying them like he would with others, and if a girl drops out of school or becomes pregnant, her case is never followed up like it would be for others simply because of who they are.

A girl living in Rubirizi Cell, Kanombe Sector, was also a victim of abuse. She was raped and became pregnant at the age of 14 by a young man who was their neighbor. She says that when she told her parents, they did nothing about it. When she asked them why, they responded that it was not a big issue and that’s how she ended up becoming a wife at that young age.

She recounts “Once I got to his house, he started mistreating me. He treated me badly, beat me every day, and told me he didn’t love me. He said he had only taken me in to avoid being imprisoned, but now he was tired of me. He constantly insulted me, reminding me that I am from a historically marginalized group.

He eventually kicked me out. I went back home and returned to making pottery. The abuse I went through was kept a secret, but it completely ruined my life.”

They request justice

A girl, who requested anonymity, told Panorama newspaper that she got pregnant at the age of 13. Her parents agreed with the man responsible and sent her to live with him. She has now given birth three times and she’s not even 18 years yet.

“I often wonder how our lives will end. Children from the Batwa community don’t get the same chances as others. Most of us give birth while still young, but it doesn’t change anything. We never attend school and neither did our parents. We also deserve justice, just like other girls.”

Culture and mentality as barriers

Mukarukwaya Alphonsine, a 68-year-old woman from Rusororo Sector, and Mvukiyehe, aged 89, both from historically marginalized backgrounds, say that in their culture, it is taboo to have a man or son-in-law imprisoned. Once a girl becomes pregnant, she is considered a mother and must give birth and support her child especially if the man is a relative.

Mukarukwaya says: “In our culture, there’s no set age for marriage or childbirth. Once a girl is 15, she should marry. Most meet their partners while digging for clay or crushing stones in quarries. Many haven’t gone to school, so they get delayed in finding partners.

A girl gives birth and learns how to care for a man. No Mutwa girl waits for laws.

And you wouldn’t report a neighbor’s son who impregnated your daughter you don’t hand him over to the police.”

Mvukiyehe adds “Imprisoning a son-in-law is forbidden. In fact, if a girl gets pregnant by a man outside the community, at least he may help lift the family out of poverty.”

What the Government Is Asked to Do

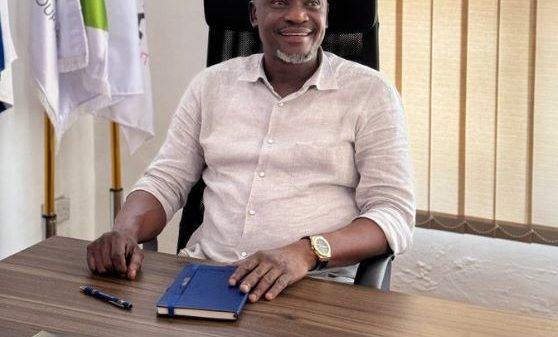

Bavakure Vincent, Executive Secretary of the Rwandan Potters’ Association, says child sexual abuse and early marriages deeply affect their community. He calls on the government to step up efforts in teaching reproductive health and legal rights.

“This group needs special attention. They lack confidence and rarely report abuse because of generational trauma and fear of stigma in society. That’s why many of their children drop out of school.

How often do you hear of a Batwa wedding? Is it because no one considers them? Are they rejected and end up marrying among themselves? And when a girl is impregnated by a relative, they just start living together but when it’s an outsider, he abandons her.”

“The problem is made worse by ignorance of the law and cultural beliefs. Many in these families never went to school they think life begins and ends with pottery. We constantly need to educate them.”

What Local Authorities Say?

Emmanuel Ndayishimiye, village leader of Kinyana, says many children from these families are often drunk, sometimes with alcohol provided by their own parents leading to abuse within the household.

“Children are neglected. Most of their parents are single mothers who drink and have sex in front of their kids.

That’s what the child sees and copies. They marry among themselves and engage in survival behaviors at a very young age.

Some parents let their children sleep outside. Who would report the abuser if even the parents don’t care?”

Nsabimana Matabishi Désiré, Executive Secretary of Rusororo Sector, says they try to help the historically marginalized integrate into society but cultural beliefs hold them back.

“These people still struggle with their mindset. They don’t believe they should seek justice or abandon the outdated thinking that once a girl’s breasts develop, she should marry.

They don’t report abuse. They believe no one should prosecute a man who impregnated their daughter.

We’re working to follow up daily in their village. They are Rwandans like everyone else they must learn to live like others.”

Sexual Violence Statistics & the Law

According to Rwanda Investigation Bureau (RIB), reported cases of child sexual abuse in Gasabo District rose dramatically from 1,064 cases in 2018 to 12,840 in 2021, a 60% increase.

Law relating about defilement (Article 133, Law No. 68/2018) says that:

- Anyone who commits sexual acts with a child (defined as anyone under 18) including penetration or acts for sexual gratification is guilty of defilement.

- If the victim is under 14, the perpetrator is sentenced to life imprisonment, without mitigation.

- If the victim is 14 or older, and the act results in a chronic illness or disability, or if cohabitation followed the abuse, the penalty is also life imprisonment.

If the act occurs between minors over 14, and no force or threats were used, no penalty applies. However, if a minor aged 14–17 defiles a child under 14, penalties under Article 54 apply.